Review of the EU Guidelines on PKU

In the first of two juicy sessions on policy and campaigning, Prof. Anita MacDonald OBE, Consultant Metabolic Dietitian at Birmingham Children’s Hospital, gave us a reassuring and sometimes sobering insight into the first revision of the European Guidelines for PKU.

(You can find more from the 2024 NSPKU conference here.)

The guidelines, published in 2017, aimed to optimise PKU treatment across the bloc. Between 2017 and 2024, they were accessed 73,000 times from countries around the globe. The accompanying dietary handbook, published in 2020, has been downloaded 78,000 times.

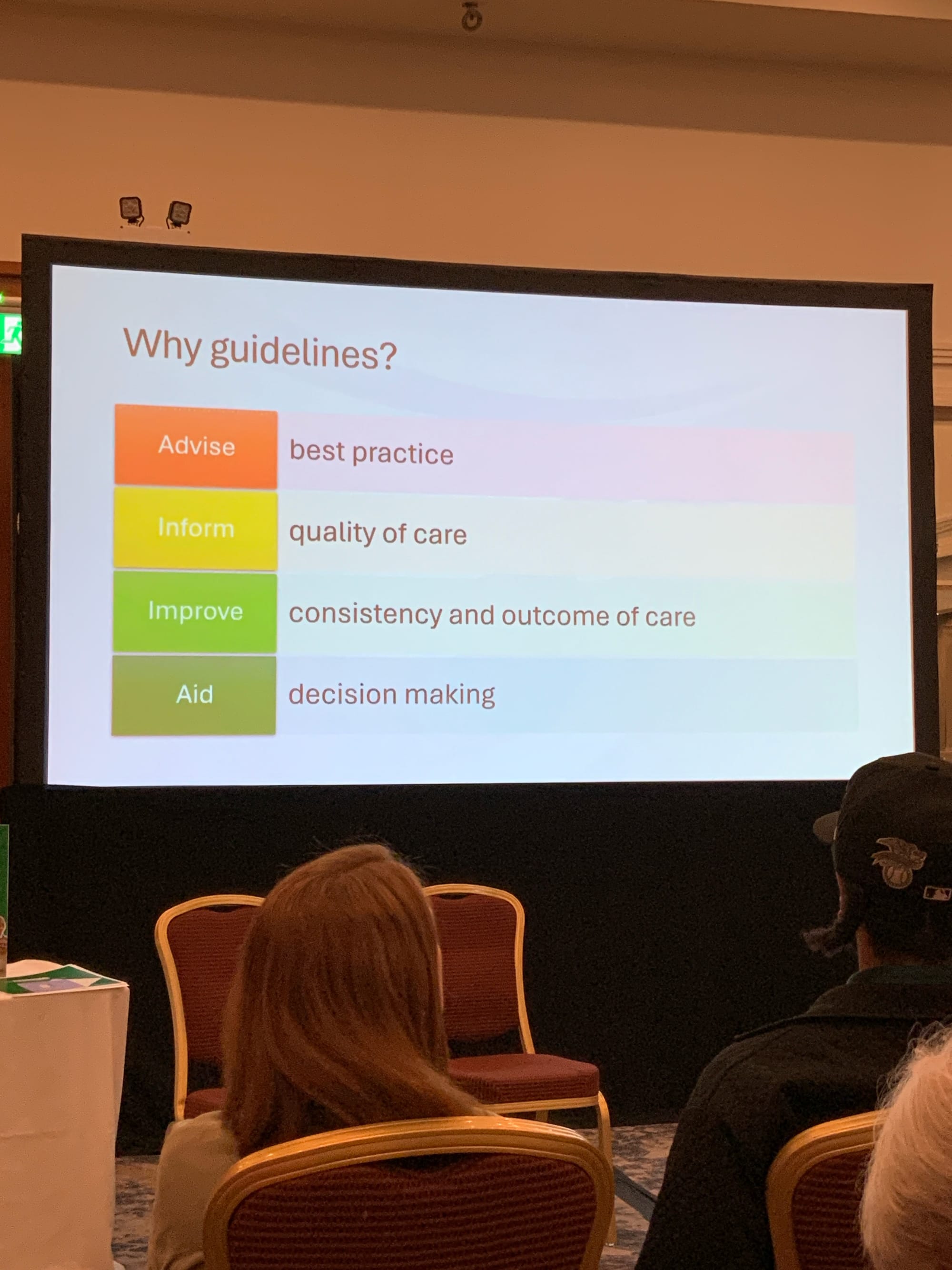

What are the European Guidelines for?

Professor MacDonald noted that the documents were especially useful in countries without established support. This was our first sobering moment of the presentation—a reminder that PKU is not tested for in some countries, leaving undiagnosed families to struggle. In other countries, the cost of healthcare or difficulties accessing treatment mean that even those diagnosed are unable to access the necessary care.

One of the key reasons for having the guidelines is to help inform policy changes and establish the best treatment practices in places where those are still being developed, and to support those in areas where treatment falls short.

Why Review the European Guidelines on PKU?

The guidelines caused controversy when first published, particularly regarding the recommended levels of phenylalanine (phe) in the blood. Critics of the guidelines were invited to contribute to this first review.

There is also the obvious reason that research has moved on markedly in the last decade. The guidelines are seven years old at the time of this first review. But the research which fed into them was conducted at least a decade ago.

How Will the Review Be Conducted?

The experts contributing to this review were assigned to one of four working groups, each focusing on different areas:

- All aspects of Nutrition,

- Comparing treatment outcomes and blood phe target ranges,

- Treating maternal PKU and those with a late diagnosis,

- Diagnostic techniques and pharmacological treatments (like pegvaliase or sapropterin)

The groups systematically reviewed all research up to 2020. This included looking at the methodology and outcomes in each paper used for each guideline. The review will also ensure that each guideline has quality evidence backing it up. Each guideline must receive at least 75% consensus by all the experts for it to be accepted into the final guideline paper.

Possible guidelines

Note: The review is ongoing, these are not confirmed at the time of publication! I include them here to demonstrate the scope of the guidelines.

Blood phe levels

There will continue to be guidelines regarding the levels of phe in the blood. It is likely that recommended phe levels for children and teenagers remain as:

- Under 12 years = 120-360umol/L;

- 12–18 years = 120-600umol/L

However, the recommended levels for adults over 18 are still causing controversy. Key findings which are being considered in the review include:

- Adult blood phe has been shown to influence brain function, and;

- keeping levels under 600umol/L does have less negative influence on the brain

- However, recent studies (Aitkenhead, 2021; and Feldmann, 2019) have found normal brain functions at higher levels in some adults.

Time considerations

There is a sobering addition to the debate for older adults with PKU: “it is unknown if there will be enhanced sensitivity to phe in ageing brains.” (MacDonald, presentation to NSPKU conference, May 2024.)

There may also be a recommendation that laboratories should report any blood phe results within two working days of receiving the sample. It discovered that this is not happening for some in the UK, even allowing for postal delays which are beyond the control of both patient and labs.

Blood phe levels and reporting is an active area of discussion for the review’s experts, and it will be interesting to see the final guideline.

Refugees and PKU

There is likely to be a recommendation that refugees from countries without newborn screening are checked for PKU. This is likely to be a guideline without controversy, I think all can agree it will be of benefit to both refugees and their new societies.

Annual Clinic review

One of the working groups is looking at clinics, and there may be a recommendation that all PKU patients are seen in clinic at least once a year. This may be something which those on diet in the UK take as a given, but there are countries where this is not standard practice. This recommendation may include a standard level of care during each visit:

- checking on height & weight;

- test to check blood phe, and other protein levels;

- tests to establish levels of other nutritional markers, like vitamins.

Neuropsychological assessment

This is a guideline with strong support from the experts, and so is likely to be confirmed in some form. As someone with access to a neuropsychologist through my PKU clinic, I fully support this sentiment and hope that it is included in the upcoming guidelines.

One suggestion was for routine assessments throughout development and into adulthood, including:

- testing of IQ and executive functions;

- checking for ‘non-optimal’ metabolic control;

- reported problems in the education or the workplace;

- actively assessing the patient’s quality of life;

- actively looking for mental health, behavioural, or social problems with referrals where needed.

There were calls for all of those with PKU to have access to a metabolic physician, a dietitian, and a neuropsychologist.

Healthy eating and exercise

There were several draft guidelines relating to healthy eating and exercise with PKU. Again, these are draft guidelines, so we do not know what the final recommendations will be. However, it was noted that:

- there is no evidence that the PKU diet causes people to be overweight or obese, but;

- as more people in general are becoming overweight, there is a similar increase in the number of people with PKU who are overweight, meaning;

- people with PKU need clear, preventative lifestyle strategies to prevent weight gain, similar to those lifestyle changes needed in the wider population.

As part of this, people with PKU should be encouraged to have active lifestyles, or take up sports, including assistance with getting adequate nutrition and energy. Professor MacDonald noted some key points here:

- people with PKU should not avoid sports because of PKU;

- ideally, take our supplements at least three different times, spaced event across the day;

- taking one of these supplements within an hour after exercise can help to refuel.

PKU foods, dentistry, and associated costs

The guidelines will also look at the specialised foods for PKU. There will likely be a recommendation that all specialised foods must meet the dietary limits on fat, sugar, and salt guidelines as that for regular foods.

Tied into this, the experts were also looking at dental care. They have found good evidence that people with PKU are at increased risk of teeth problems. This means encouraging those with PKU or those caring for kids with PKU to have good dental routines and to seek advice early.

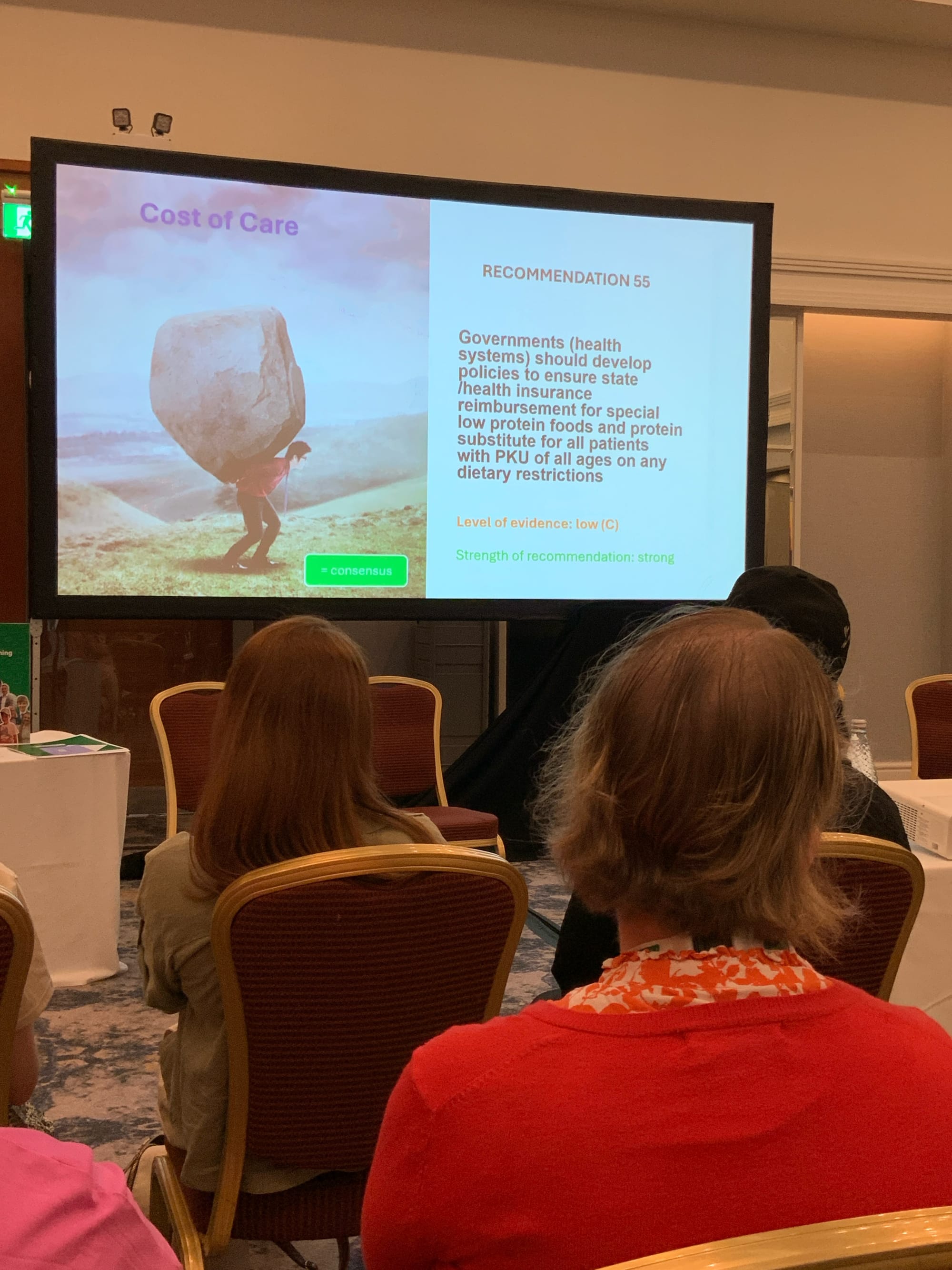

In the UK, the NHS covers the cost of most PKU supplements and specialised foods. This is not the case across Europe, and is an area under review in these guidelines. There is likely to be a recommendation that states across Europe should reimburse people with PKU for these essential medical supplies.

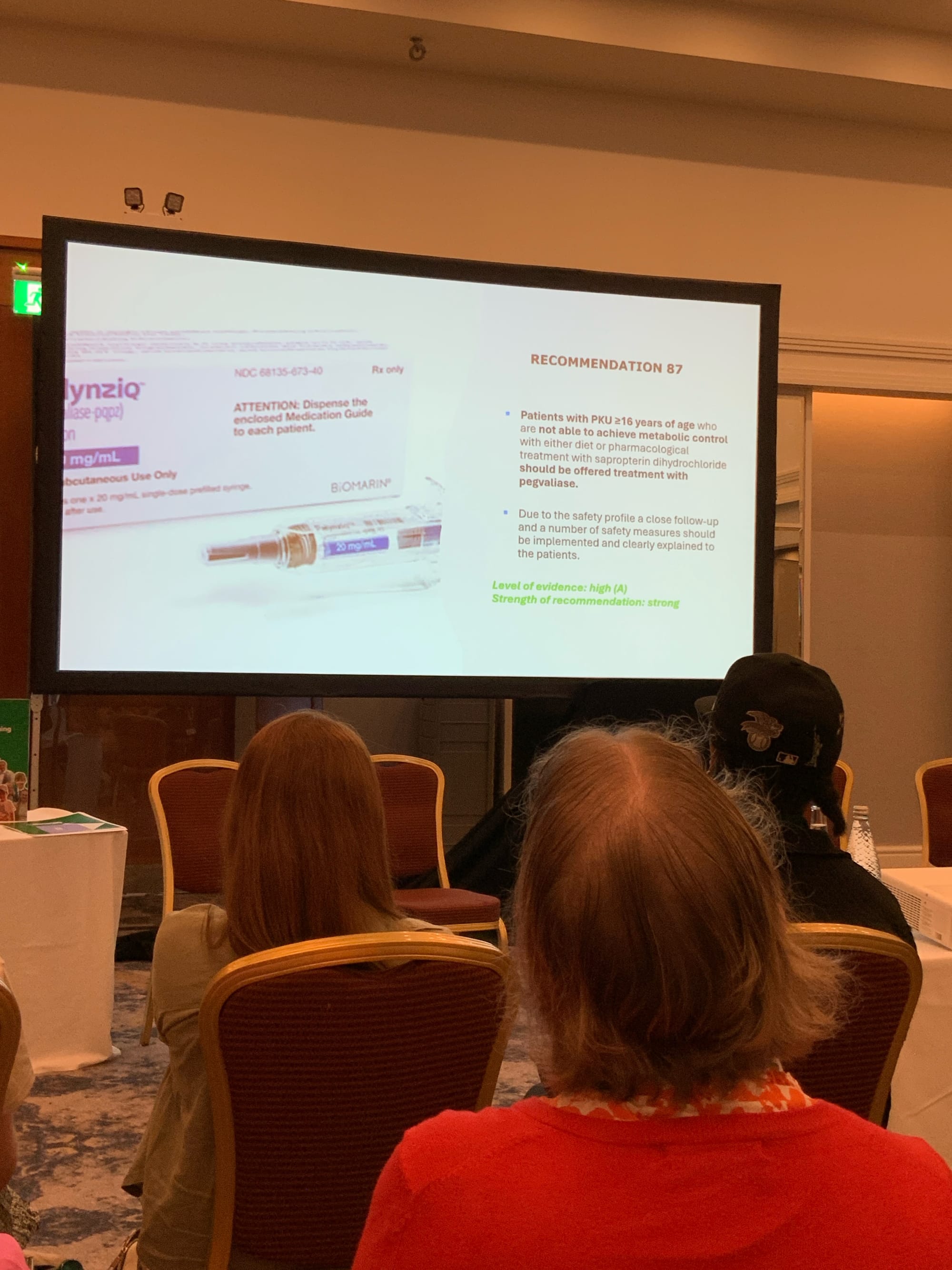

Treatments beyond the PKU restricted diet & sapropterin

I finish this round up with a look at a draft recommendation close to my heart, and one with strong support from the experts. The review is likely to recommend that those over 16 who are struggling on either the restricted diet or sapropterin (hullo!) should be offered treatment with pegvaliase. (This is the injection known as Palynziq, and you can find out more about it here.)

This is great news! But those of us in the UK cannot get too excited. While pegvaliase has been available in the EU for some years now, the UK is no longer in the EU (insert expletive here).

The makers of pegvaliase have pointed out that it is unlikely to be available in the UK anytime soon. So, while a recommendation on this is welcome, there will still be much campaigning for those in the UK.

The NSPKU is already on the case, and I’ll report on that in the next blog.

Member discussion