The origins of PKU treatment

PKU was discovered in 1934, but was considered untreatable for decades. Then, a team at the Birmingham Children’s Hospital took up the challenge. Prof. Anita MacDonald showed me round the BCH for an afternoon of PKU legends, both past and present.

Mary and Sheila Jones

Birmingham Children’s Hospital (BCH) set up a screening programme for PKU in the early 1950s. The team had a positive result on their third test, a young girl named Sheila. Sheila’s mother, Mary, knew that something was impairing the development of her third child. Concern led her to her local doctor, who in turn referred Sheila on to the Birmingham Children’s hospital.

Mary's persistence drove the doctors to develop a treatment for PKU

The clinical were thrilled to have discovered a patient with this condition so quickly in their trial. Mary Jones was more interested in a treatment for her daughter, and simply would not accept that there was no therapy for this rare condition. It was her persistence which drove the doctors to develop a treatment for PKU.

Remembering Sheila, the first patient treated for PKU

In 2023, the European Society for Phenylketonuria and Allied Disorders Treated as Phenylketonuria (or E.S.PKU) held its annual conference in Birmingham to commemorate 50 years of a treatment for PKU. A plaque commemorating Sheila, her mother Mary, and the clinical team was unveiled at the BCH during the conference.

Professor Anita MacDonald told me of the desire to ensure that the legacy of Sheila and the BCH team would be recognised for future PKU generations too. The plaque was unveiled by Sheila’s brother, Trevor Jones, who said that even he was not aware of “how big a contribution Sheila and my mum made around the world, I’m so in awe of them.”

The BCH team working on a treatment for PKU

Dr Evelyn Hickmans had established the Biochemistry laboratory at Birmingham Children’s Hospital in 1923. Dr Hickmans was a formidable lady who poured her knowledge and experience into setting up the BCH laboratory in the inter-year wars.

Dr Horst Bickel had a PhD in Aminoaciduria, or the study of unusual proportions of amino acid indicators in urine. This meant he also had knowledge of the chromatographic techniques required to measure them. It was Bickel who would operate the charcoal filtration system used to synthesise the first treatment for PKU. (See below.)

Dr John Gerrard worked at BCH following wartime service in the Royal Army Medical Corps. He was part of the team developing the PKU treatment before leaving for a career in Canada.

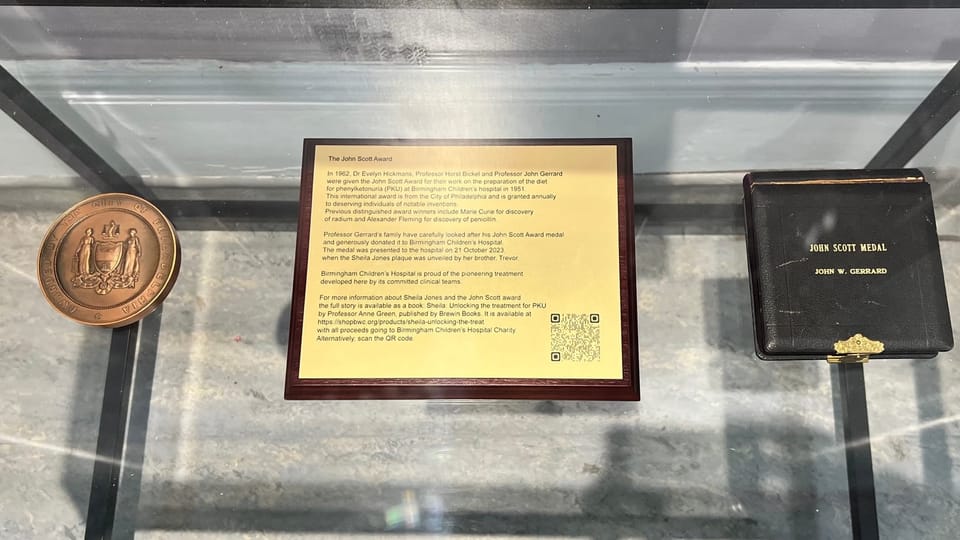

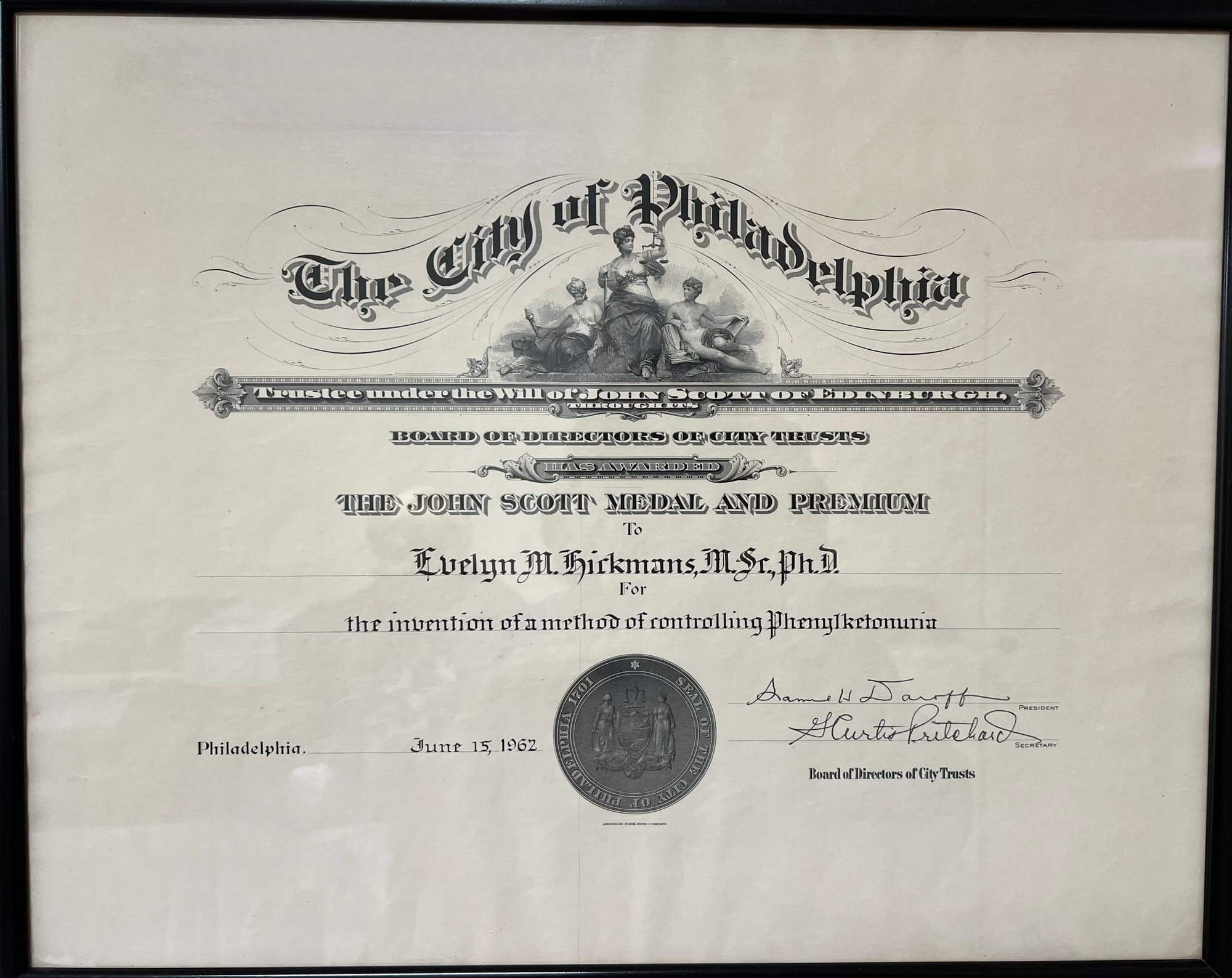

The John Scott Medal

Drs Gerrard, Bickel, and Hickmans received the prestigious John Scott medal in 1962 for their work on developing a PKU treatment. (Pictured in the title photo.) The John Scott Medal was created in 1816, to be presented to men and women whose inventions significantly improved the "comfort, welfare, and happiness of humankind". Previous recipients include Marie Curie, the Wright Brothers, and Nikola Tesla.

Removing phe from the diet

Adjusting the amino acid level in food was not entirely unprecedented. A method for removing phe from natural protein had been developed in the United States. This was achieved by first breaking a natural protein down into the constituent amino acids, and then filtering out the phe. However, this was the first time anyone had attempted to remove phe from food for the purposes of treating PKU. Fortunately, there was a source of expertise in the UK.

Dr Louis Woolfe worked at Great Ormond Street Hospital. He had experience of breaking down a milk protein into constituent amino acids to treat malnutrition. Dr Woolfe had already realised his technique may be useful in treating PKU, but had yet to find an opportunity to do so. When contacted by the team at Birmingham Children’s Hospital, he shared his expertise with Dr Hickmans and her team in the hospital laboratory.

Filtering out protein

The team filtered a protein derived from milk through activated charcoal to remove phenylalanine. This was a messy job, and Bickel was banished to the hospital basement when the formula needed to be prepared. The milk was filtered through a Professor-MacDonald-sized glass column (see photo below), which removed some amino acids, including phe. The other essential amino acids were added back into the formula to provide a complete, if unpleasant, treatment for Sheila.

The legacy at BCH

A worthy reminder of the thousands of lives improved by the efforts of these pioneers in PKU treatment.

Many thanks to Professor MacDonald for her turn as a charming and knowledgeable tour guide (another talent for the CV!). This homage to the home of PKU treatment was of personal importance for me and my family. It was also a worthy reminder of the thousands of lives improved by the efforts of these pioneers in PKU treatment.

I was touched to see that BCH do commemorate their legacy in the halls of a bustling hospital. The history sits comfortably with the cutting-edge research and trials undertaken in a modern clinic, which continues to be a model of excellent for PKU treatment.

However, the living legacy of PKU legends such as Hickmans, Bickel, Gerrard, Wolfe, Guthrie, Cockburn, MacDonald, and the hundreds of other clinicians treating PKU and rare diseases remains the multitude of lives they have touched and improved.

Member discussion